How it works

- Language Mixing uses a little-known method called “Diglot Weave”.

- You mix the foreign words into English sentences.

- You pretend they they’re just newly-coined “English”

Imagine that decades ago, doctors found a particular medicine (for something or other) that might be up to twice as effective as the current medicines. Then imagine that upon hearing about this, the medical community ignored the discovery because they didn’t care. Now imagine that a few individual researchers had repeatedly confirmed its effectiveness but that the community ignored these people too.

I don’t know if such medicines exist. However, at least one method for learning second languages like that exists. It’s the method used in all Language Mixing books. It’s called the “Diglot Weave” method, but I call it language mixing.

Experiments have found it to be about twice as effective as typical language-learning methods. Yet, it has been almost entirely ignored by teachers, researchers, and publishers of language books — that is, until now.

A history

Many people have figured out the method for themselves by accident; I did too. I was trying to figure out why I found learning foreign words so tricky (almost impossible), yet I had no problem learning new English words!

Like most failed language learners, I blamed myself; I assumed that the teaching materials must be brilliant and the problem must lie with me. Sure, I can be lazy sometimes (like anyone can), but I had recently made a lot of effort and still got nowhere!

So I thought, “Well, if I have no problem learning new English words, then why don’t I just pretend that these foreign words are English too?” and that’s what I did. And it worked!

I wasn’t the first person to stumble across this method.

The first person to figure it out and put it in writing was (probably) Robbins Burling from the University of Michigan in 1968. He wrote a paper called “Some Outlandish Proposals for the Teaching of Foreign Languages”. His “Outlandish Proposals” were various ways of using this method. He’s the one who named it Diglot Weave.[1]

What exactly is it?

You gradually mix (or weave) the words, phrases, and grammar rules of another language into your native language. You essentially adopt them into your native tongue like loanwords. The name is “Diglot Weave” because “Diglot” means “two languages”, and you mix or “weave” them together.

Yes, you pretend that words from your target language are newly-coined English synonyms. You could imagine the word is new slang or a new trendy term all the kids are saying. Your brain is tricked into accepting foreign words as new ‘English’ words. This method feels very easy since we’re always learning new English words (as people constantly coin new ones).

For example, when learning Spanish, you could pretend that “hombre” is just another English word for “man” and use it in fully-English sentences. When learning German, you could pretend that “Frau” is just another English word for “woman”, and so on. Again, you would use all these ‘new English words’ in otherwise fully-English sentences.

The hombre met the woman.

The man met the Frau.

It even works with grammar.

For example, many languages would say “a car blue” instead of “a blue car”. So you would read, hear, or write English sentences using that grammar rule until it sounded normal to your ears. After a while, it no longer sounds weird or ‘foreign’; instead, it sounds entirely normal. Indeed, it may sound like an excellent way to speak English!

Other people will think you sound very strange if you mix foreign words and grammar rules into your everyday English. So, instead, it’s better to blend these “new English words” and grammar rules into written English or to find a learning buddy doing the same thing.

My books provide pieces of foreign languages already mixed into English text.

Experiments

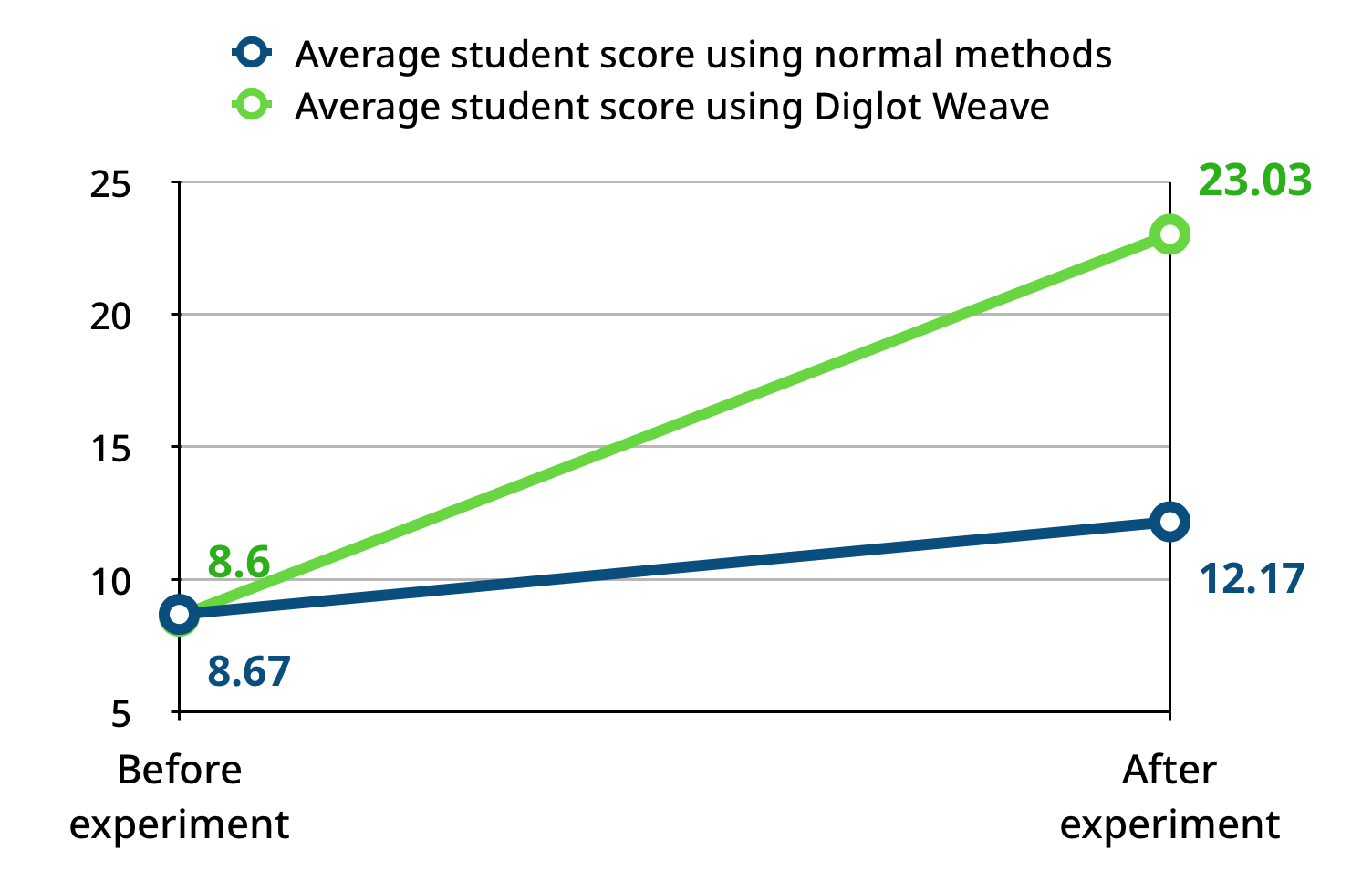

Years before I published these books, one university in Iran experimented with the Diglot Weave method on some high schoolers learning English. Half the kids learned using standard methods, and the other half used the Diglot Weave method. Afterwards, they all sat a test. What were the results?

The kids taught the usual way scored 12 out of 25, but those taught with the Diglot Weave method scored nearly double – 23 out of 25![2]

Figure 1. The result of the study by Azadeh Nemati

Also, some pre-schools in China use the method to teach children English. They mix English words into fairy tales otherwise entirely written in Chinese (such as a Chinese translation of Little Red Riding Hood). The students enjoy it much more than the usual approaches, and the teachers report better results overall. Parents also appreciate it because, in ultra-competitive China, they see their children learning English more quickly and easily than other children.[3]

Annoyingly unavailable

When I first figured out what Robbins Burling had already found (and named “Diglot Weave”), I got very excited and wanted to try it out.

So I chose a language I knew nothing about (and found incomprehensible): Danish. I watched television shows in the language for a few hours and found Danish to be as clear as mud.

Then, I scribbled down a list of the most common little words that we use in everyday speech (words like “and”, “with”, “the”, and so on) alongside their Danish equivalents (taken from a dictionary).

Now armed with my list as a reference, I wrote down many English sentences with the Danish words mixed in. After doing this on and off for two weeks, I tried watching TV in that language again.

What happened?

I couldn’t believe it! I could actually follow what was going on! At least, roughly. Sometimes I could follow things clearly, sometimes not at all, but overall, I could ‘get the gist’. I was stunned. I had always thought I was bad at languages, and just two weeks earlier, I couldn’t grasp anything whatsoever.

I had studied Portuguese for several years and still understood little or nothing from the spoken language. It took me four or five years to understand most written Portuguese sentences (and I never understood their nightmarish verbs). Yet here I was, just two weeks into a new language, and I could (more or less) follow it!

So was I really “bad at languages”? I don’t think so. I think that the normal methods were just bad for me.

Yes, my little experiment worked, and I was pleased, but there was more; it felt very easy. I wasn’t feeling confused, frustrated, or falling asleep from boredom; I was enjoying it! It didn’t feel like the usual language-learning chore.

So, I wanted more!

Yet, there wasn’t any more.

I couldn’t just jump on Amazon and buy a book using this method, because I couldn’t find any, at least not back then. If I wanted to use this method, I’d have to plan everything myself from scratch.

So I spent several years cobbling together different prototype books for learning languages using this method. I tried many other formats before settling on the format I’m publishing now, but I think (and hope) I’ve finally got it right.

How your target language will transform into ‘English’

My books will help you to adopt parts of other languages into your brain as “English”.

After completing these books, the words you have adopted will begin to feel like “English” and will feel more and more like “English” the more you see them mixed into English. Then whenever you hear native speakers saying what you’ve adopted in my books, the words will pop out at you as if they were English loanwords.

Then, if you keep reading more Mixing books (there are many planned), most foreign sentences will feel and sound like they contain many ‘English’ loanwords, at least, to you.

From your perspective, your target language will eventually feel and sound no more ‘foreign’ than a strong English dialect.

Is this just a theory? Not really. Not only has this method been confirmed by experiment, but English speakers have been doing this for centuries – without knowing it!

Tried and tested

You have already used this method many times. Indeed, you use it whenever you learn a new English word!

For example, The Oxford English Dictionary now adds new entries four times a year. In March 2015 alone, it gained 207 completely new words. Many are just existing words combined or changed in some way, but some come from foreign languages.

Indeed, English has adopted many common words from foreign languages in recent decades. For example:

- “Karate” from Japanese,

- “Parkour” from French,

- “Robot” from Czech,

- “Glitch” from Yiddish,

- “Tofu” from Chinese,

- “Macho” from Spanish,

- And many hundreds more!

The older you are, the more foreign words you’ve adopted – even if you’ve never purposely learned a foreign language.

How did we all adopt these new words? English speakers mixed these new words into fully English sentences, transforming them into English words.

Well, that’s exactly what we’ll be doing with a foreign language in these books!

Yet, it goes much further.

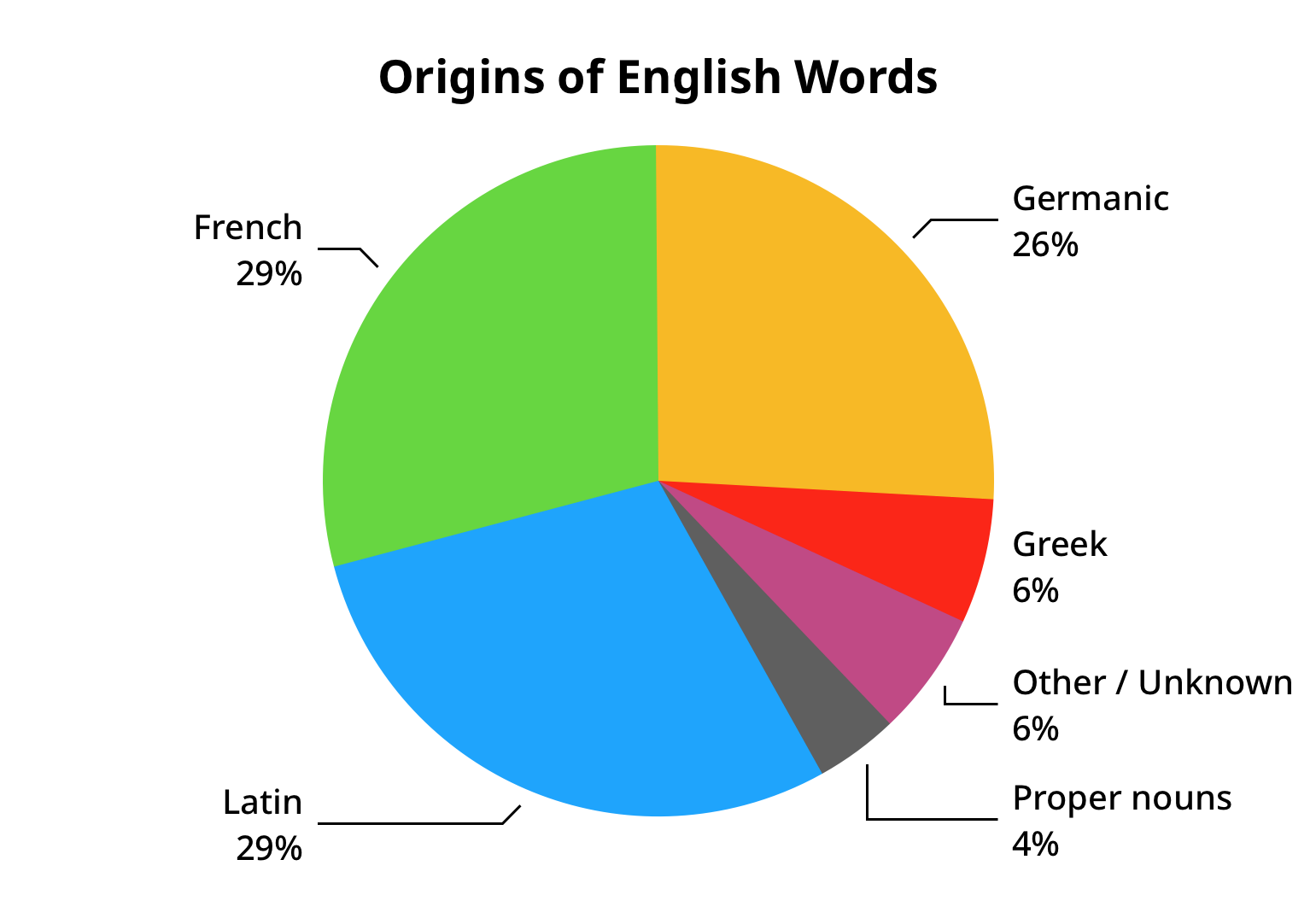

This method created Modern English

Originally, our English language began as just another branch of the Germanic language. However, over time, English adopted hundreds of thousands of words from languages such as Latin, French, and Greek. Today, only about 1 out of 4 English words come from Germanic. In other words, about 3 out of 4 modern “English” words were “foreign” until English speakers adopted them.[4]

Figure 2. This pie chart shows English words’ different origins according to a 1973 book by Thomas Finkenstaedt and Dieter Wolff.

Therefore, this method is neither new nor strange. It is, in fact, normal and natural; it’s something that you’ve used throughout your entire life; it even created the modern English language! Millions have used it for millennia – without even thinking about it.

Words, not codes

I believe there’s an overlooked reason why learning another language is difficult. I think that the usual language-learning methods turn the words of your target language into a secret code. Each word stops being a word and becomes no different to a telephone number or a password.

I believe that when we use standard methods to remember (for example) that “bonjour” means “hello”, we’re not learning that “bonjour” is “hello”; we’re learning that “bonjour” is a code-word representing “hello”.

And this causes a struggle in our brains, making learning more difficult.

Indeed, many popular language-learning techniques and phone apps turn language learning into memory games. They get you to memorise foreign words in the same way that American police officers memorise police codes (e.g. 10-4 means “affirmative”).

They don’t give you words to use; they give you codes to memorise.

The problem is that our brains are not using our typical speech centres but are sharing the burden with brain areas for remembering codes. We then under-utilise the tremendous built-in advantages of our speech centres. Is this why people who find language learning easy tend to be memory champions? If so, people with ordinary memory skills will struggle (like me).

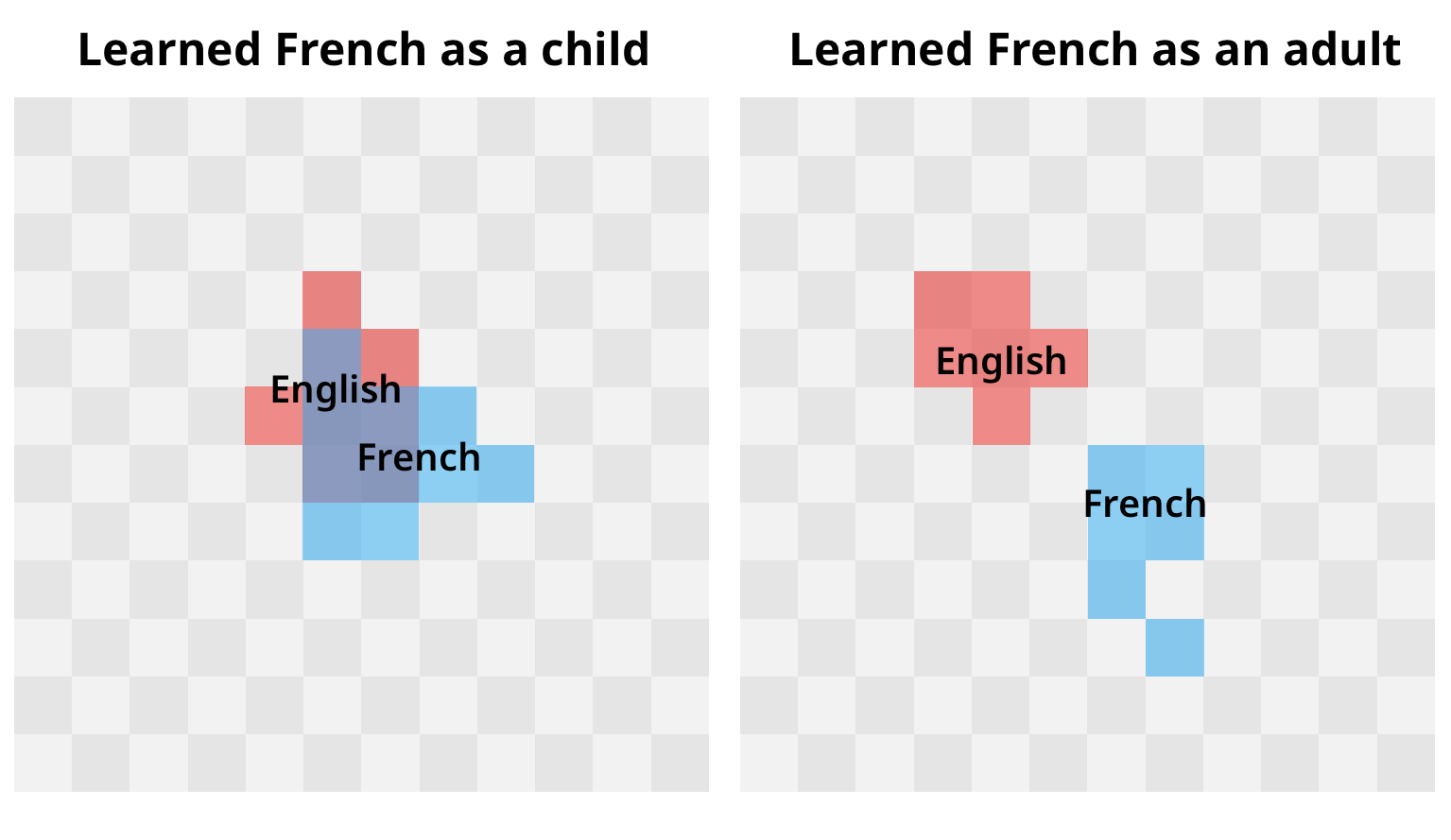

Am I right? Perhaps! Researchers have performed brain scans on language learners and found exactly what I would expect. They scanned the brains of people while they spoke their second language to see which parts lit up. One group of volunteers were bilingual since childhood, while the other group learned a second language as an adult. These two groups showed distinct differences in their brains.[5]

Figure 3. Brain activity in two different bilingual people.

This diagram represents a typical finding.[6] It shows a zoomed-in scan of a small brain area in two volunteers. The colours indicate their brain activity when they spoke their two languages. The parts of their brain marked in red lit up when they spoke English, and areas marked in blue lit up when they spoke French. Do you see the difference between the two volunteers?

The volunteer bilingual since childhood was using (pretty much) the same brain areas when speaking both English and French. However, the volunteer who learned French as an adult used physically separate brain areas from his native English.

Other volunteers showed these same patterns.

What does this mean?

Well, it shows that those who have been bilingual since childhood have both languages living together, sharing the same resources in the same space. Yet adult language learners use different parts of the brain, and lose the advantages of pooling resources with their native tongue.

I believe this explains why this method feels so much easier than the standard methods. We’re adopting foreign words into our existing vocabulary. We’re just using the same old brain areas we’ve always used to speak – just like people who have been bilingual since childhood. Your brain doesn’t need to recruit additional brain areas; it’s already using everything it needs.

Of course, I might be wrong; I am not a brain expert! But the bottom line is this: This method both works better and feels easier – and this might be the reason why: something radically different is happening in our brains.

The Mixing books

This prompts the question: what’s the best way to use this method?

My strategy is to adopt the most commonly-used words and grammar rules. It would be silly to adopt the foreign-language term for anachronistic before adopting the word for and.

Indeed, if you start with the most common terms, you’ll quickly understand many words in most sentences. One study found that just 1,000 words covered 89% of popular English writing. That’s not many. Over a year, 1,000 words are just 2.7 per day.

Therefore, my challenge is not to create books that include as many words as possible – no, it’s to teach the most useful words before you get bored with me.

Further, these books are arranged into sensible categories. You can choose which one you want to learn first and last. They are:

- Little Words (e.g. “and”, “with”)

- Nouns (names of things)

- Adjectives (describing words)

- You, Me, & Others (pronouns)

- Questions & Expressions

- Verbs (mostly verb endings)

- More Verbs

Each book covers 30 to 40 parts of the target language. I will write further books on various specific topics, such as numbers and dates, work, school, history, sports, etc.

The plan is to eventually create enough books to cover at least 1,000 common parts of each language. However, even just a handful of these books might be enough to kickstart your learning, especially if you’re already exposed to the language through work or family.

After you’ve adopted many of the foreign words and grammar rules, it may feel like you vaguely remember a grandparent speaking to you in the language when you were young. You can understand it but wouldn’t call yourself fluent – yet.

Then, something magical will begin to happen!

The words you haven’t adopted yet will appear (at least, to you) to be surrounded by “English”! Yes, all content in the target language that you read or hear will feel like a Mixing course because most of the words will feel like ‘English’ by that point, with new words mixed in between.

Once you reach that level, learning more of your target language will become an automatic process. All you then need is enough exposure to the language; given time, you will develop more and more fluency until it feels as natural as your native English language.

In a sense, it will then become your second native language. It may feel like you’ve been somewhat bilingual since childhood. After all, to your brain, it will be no different from English.

That’s pretty amazing.

References

[^1] “Some Outlandish Proposals For Teaching Foreign Languages” by Robbins Burling (University of Michigan) Language Learning 18 (June 1968) 61-76. doi:10.1111/j.1467‑1770.1987.tb00390.x

[^2] “The Effect of Teaching Vocabulary through the Diglot-Weave Technique on Vocabulary Learning of Iranian High School Students” by Azadeh Nemati (Islamic Azad University) and Ensieh Maleki (Payame-Nour University). Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences 98 (2014) 1340 – 1345. doi:10.1016/j.sbspro.2014.03.551

[^3] “Communicative Language-Teaching through Sandwich Stories” by Yuhua Ji. TESL Canada Journal / Revue TESL du Canada Vol. 17 (Winter 1999) 103-113. doi:10.1017/S0266078402001049

[^4] Ordered profusion; studies in dictionaries and the English lexicon by Thomas Finkenstaedt and Dieter Wolff (1973). ISBN 3-533-02253-6

[^5] “Distinct cortical areas associated with native and second languages” by Kim, K., Relkin, N., Lee, KM. et al. Nature 388, 171–174 (1997). https://doi.org/10.1038/40623

[^6] Licensing restrictions prevent me from showing the real scans, so this is an “artists impression” that just looks similar. You’ll need to consult the original academic paper to see the real scans.

Mailing List

Get notified of new releases, and other interesting tidbits.

Unsubscribe at any time.

See previous e-mails.